College, students with autism, and STEM careers. Editorial Board Member Theresa Revans-McMenimon takes a broad look at how the needs of college students who have autism and the STEM workforce overlap. Neurodivergent young professionals and job seekers have a lot to contribute to companies, and studies show that investments in diversity and inclusion pay off in ways much more nuanced than merely finding an employee skilled at any one particular job. Read on to learn more about the issues and challenges and what can be done to support students as they begin looking for jobs and joining the workforce.

In 2015, the United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon, launched a call to action by inviting businesses to offer concrete initiatives to employ people with autism because most people who have autism are unemployed. In their study, “Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Participation Among College Students with an Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Wei, Yu, Shattuck, McCracken, and Blackorby (2013) cited the National Science Board’s 2020 Vision for the National Science Foundation, pointing out that the STEM workforce plays an important part in U.S. economic and global considerations. The vision statement calls for the promotion of STEM training and employment opportunities in the United States in order for the US to maintain a leadership role in a global economy. So, where do these two messages intersect?

By tapping into the talent pool of STEM students who have autism, we can help generate a trained workforce that can compete in the global economy. To increase the size of this talent pool, we need to attend to the students not transitioning to post-secondary education, provide them with the necessary supports to succeed in college, and then help students make the successful leap to employment.

Exploring the Needs of Post-Secondary Students Who Have Autism

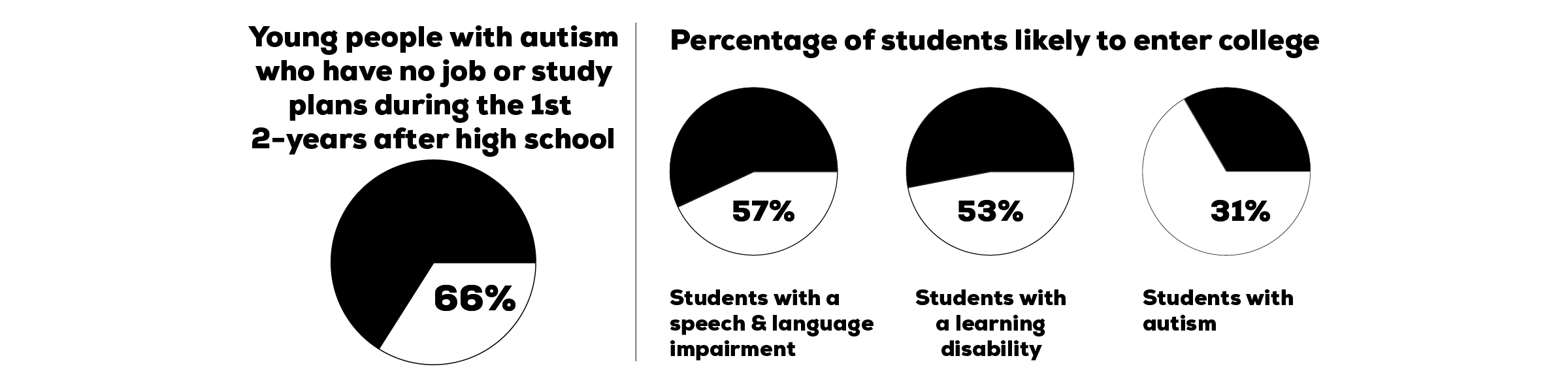

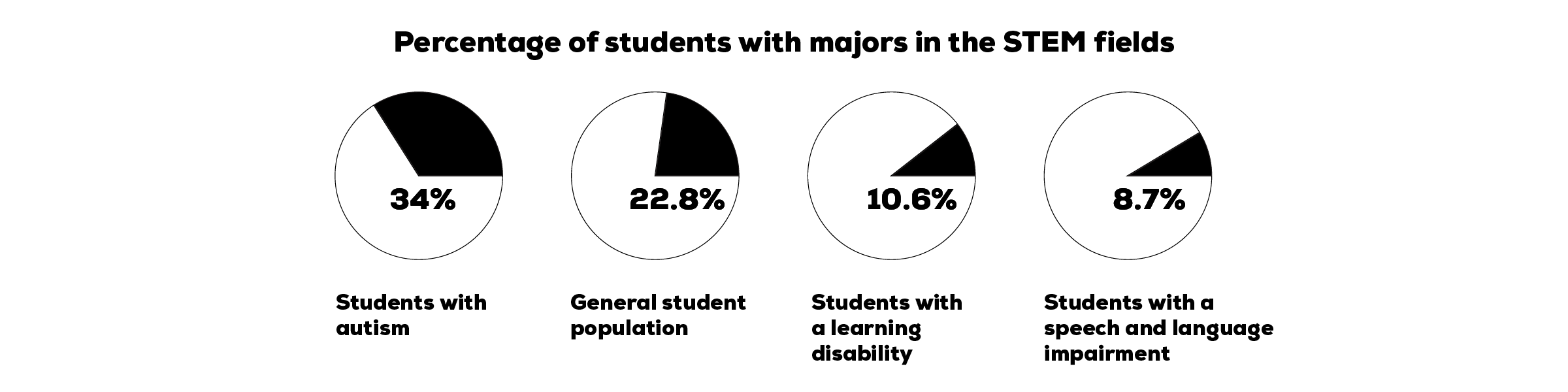

We first need some background information on students with autism transitioning to post-secondary education. The research that Wei et al. (2013) conducted revealed that students with autism were less likely to enter two- or four-year colleges compared to other disability groups. Fifty-three percent of students with a learning disability and fifty-seven percent of students with a speech and language disability were likely to enter college compared to thirty-one percent with an autism spectrum diagnosis.

In the community college where this writer works, out of the 1600 self-identified students with disabilities who are registered, only 120 identify as having autism. That is seven and a half percent!

For their article “Post-school Needs of Young People with High-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder” (2015), Neary, Gilmore, and Ashburner surveyed parents in Australia regarding the key areas where they reported difficulties or barriers preventing success in post-secondary settings. The top four areas are:

- struggles with organization,

- low motivation,

- failing of exams or assignments once the student begins school, and

- the lack of formal support in a post-secondary setting.

The article then goes on to cite issues in Britain where factors such as

- negotiating the educational community,

- social and sensory difficulties, and

- difficulties in executive functioning

have hindered academic progress.

In the U.S., students with autism who do not engage in college were three times more likely to have no daytime activities. They also spend a higher number of hours on video games than any other disability cohort. While gaming can be positive for students with autism, the discrepancy in usage suggests that emerging young adults without college or workforce options may lack outlets for their talents and ambitions. As Maanvi Singh (2015) writes in an article for NPR, “two thirds of young people with autism had neither a job nor educational plans during the first two years after high school.” The academic failure of two thirds of students with autism is a pandemic issue.

Assisting with the Transition to College

Transition planning and social skills training can address these issues. Wei et al. (2013) state that “changes in routine and exposure to new and larger social dynamics can derail a person with ASD even in familiar settings.” However, exposing students to the next steps after high school, i.e., college tours and visits, career assessments and exploration, and informational interviews, can make the unfamiliar familiar. And this familiarity can help ease the transition. However, students with autism may need extra assistance with organizational and time management techniques that aide with college success. Role-playing exercises around social skills, education on students’ rights under the ADA, and how accommodations are administered in a college setting are also key.

Once a student has enrolled in college, continued support can keep the momentum going. Participating in social skills support groups and clubs on campus, as well as accessing tutoring and academic support, are ingredients for success. It is also essential to participate in additional career assessments to help students find a major and engage in state vocational rehabilitation services. Career assessments will help to identify an individual’s strengths and interests and help point them towards a career where they can experience success. State vocational rehabilitation (VR) agencies are government funded and can assist individuals with disabilities with employment and training. To find a local VR agency, log onto www.askjan.org (Job Action Network).

Of the thirty-one percent of students with autism who enter college, thirty-four percent chose majors in the STEM fields, compared to 8.7 percent of students with a learning disability and 10.6 percent of students with a speech and language impairment. The rate of students with autism in STEM majors is higher than the 22.8 percent of the general population of students. Therefore, “Post-secondary educational institutions need to provide extra supports and services for students with autism to complete their college degrees and navigate toward STEM careers” (Wei et al., 2013). The success of practices and programs profiled on STS, as well as represented by STS contributors, indicates that these are achievable goals for all institutions of higher education.

Transition to Employment

So, once an individual has received supports to complete their training and degree in the STEM field, how can we further support the student on their journey towards successful with employment? What types of employment are there?

- “Competitive employment” is considered to be regular employment without supports.

- “Supported employment” is competitive employment with support.

- “Sheltered employment” is a long-term placement program.

Sheltered employment does not take place in a fully integrated setting and the work is often considered “bench assembly.” Individuals with post-secondary training or education would engage in either competitive or supported employment.

Lorenz, Frischling, Cuadros, and Heinitz (2016) surveyed individuals with ASD to learn of possible barriers and solutions to employment success. In their article, the researchers focused on both competitive and supportive employment.

The results of the research indicated three barriers to employment:

- social and communication difficulties,

- the formality or practical aspects of the job, and

- issues with the demands of the job.

Surveyed participants used coping strategies and sought external help for support in overcoming these barriers. Individuals in competitive employment identified communication and social issues as the number one problem area and believed they were meeting the demands of the job. On the other hand, individuals in supported employment identified job demands as the number one issue. For some, the job placement was similar to putting a square peg in a round hole.

Lorenz et al. (2016) are proposing a “more customized approach to successfully employ individuals with autism. Employment should be based on their needs and resources…strengths should be identified and fostered at the same time.” This customized approach is applicable to both competitive and supportive employment environments. Additionally, such research gives employers insight into what kinds of supports employees with autism may benefit most from – those geared toward communication or those geared toward task completion.

Meeting Individual and Economic Needs Through Education

What can we take away from these data and initiatives? First, in order to compete in the global economy, we need to increase the number of individuals entering STEM fields. People who have autism generally have contributions and talents that are categorically ignored by workforces in need. Too many people with autism are unemployed or underemployed even though they can contribute to STEM industries and initiatives. Transition planning needs to begin in high school, continue through college, and even support employment. That may sound like a lot, but the potential for positive outcomes are significant and truly impactful for everyone.

A good plan for any one family would include early exposure to and discussion about college and the opportunities that are offered. Plus, career assessments and exploration, with exposure to careers in the STEM fields, are important. Additionally, families should focus on social skills development for the workforce and social confidence. All of this should happen during a student’s high school years. Once a student is in college, academic support is essential. Preparing both hard and soft skills is imperative to achieve competitive employment. In this way, individuals can acquire specific employment for their skills and have the communication skills to navigate employment issues that may arise. These skills and the resultant experience will give today’s students greater choice of employment and flexibility for the future.

Thoughts and comments for Theresa?

Join the conversation.

You might also like our eBook, Imagine Your Future in STEM, or our posts Autism and Community College: Why it’s a Good Fit and Autistic and Transitioning to College? What Students and Families Need to Know.

References:

- Lorenz, T., Frischling, C., Cuadros, R., & Heinitz, K. (2016). Autism and overcoming job barriers: comparing job-related barriers and possible solutions in and outside of autism-specific employment. PLoS One, 11(1). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147040

- National Science Board. (2005, December). 2020 vision for the national science foundation. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED496331.pdf

- Neary, P., Gilmore, L., & Ashburner, J. (2015). Post-school needs of young people with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 18, 1-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.06.010

- Singh, M. (2015). Young adults with autism more likely to be unemployed, isolated. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/04/21/401243060/young-adults-with-autism-more-likely-to-be-unemployed-isolated

- Wei, X., Yu, J., Shattuck, P., McCracken, M., Blackorby, J. (2013). Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) participation among college students with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(7), 1539-1546. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012- 1700-z