STEM grad student Patrick Dwyer shares insight for autistic students into the social dynamics of college classrooms. College is a lot different from high school, and Patrick introduces us to some key distinctions.

When you are getting ready to attend community college or university, you may find yourself wondering what to expect in your classes – and not just in the sense of what content will be presented in lectures, but also in terms of the social expectations of the post-secondary environment. How does the social culture of the postsecondary lecture work? We often say that university is completely different from high school, but what precisely do we mean by that?

Personally, I believe that the best way of answering this question is to actually take the time to explore a post-secondary environment before your classes start. That’s what I did and it worked very well for me. However, even before we start exploring, it’s good to have some idea about what we can expect, which is where this post comes in.

I also hope to use this post to discuss some different types of classroom environments that we can see inside the post-secondary campus. Not all classes have the same culture – there’s an enormous gulf between, say, a small humanities tutorial and a giant intro science lecture.

Autonomy

Probably the biggest single difference between high school and post-secondary education is that post-secondary students are treated as adults and, accordingly, given greater autonomy. For example, nobody’s going to demand that students get permission before stepping out of a lecture to use the washroom (although, if you’re in a large class, leaving might be rather distracting to your fellow students). I once had an eccentric professor who called students out for showing up late, but that’s extremely unusual.

You should still address your professor by their title (Doctor or Professor So-and-so[1]) unless they specifically invite you to say something else, but in general, the university culture tends to be less hierarchical than the K-12 classroom.

Somebody might take attendance in the first few classes, because of the need to open up waitlist spots, but you may or may not see attendance being taken in subsequent classes. Of course, you should still attend class – your grades will suffer if you don’t! Also, attendance may still be taken in tutorials and labs, because of their smaller size and greater focus on participation.

Class Size

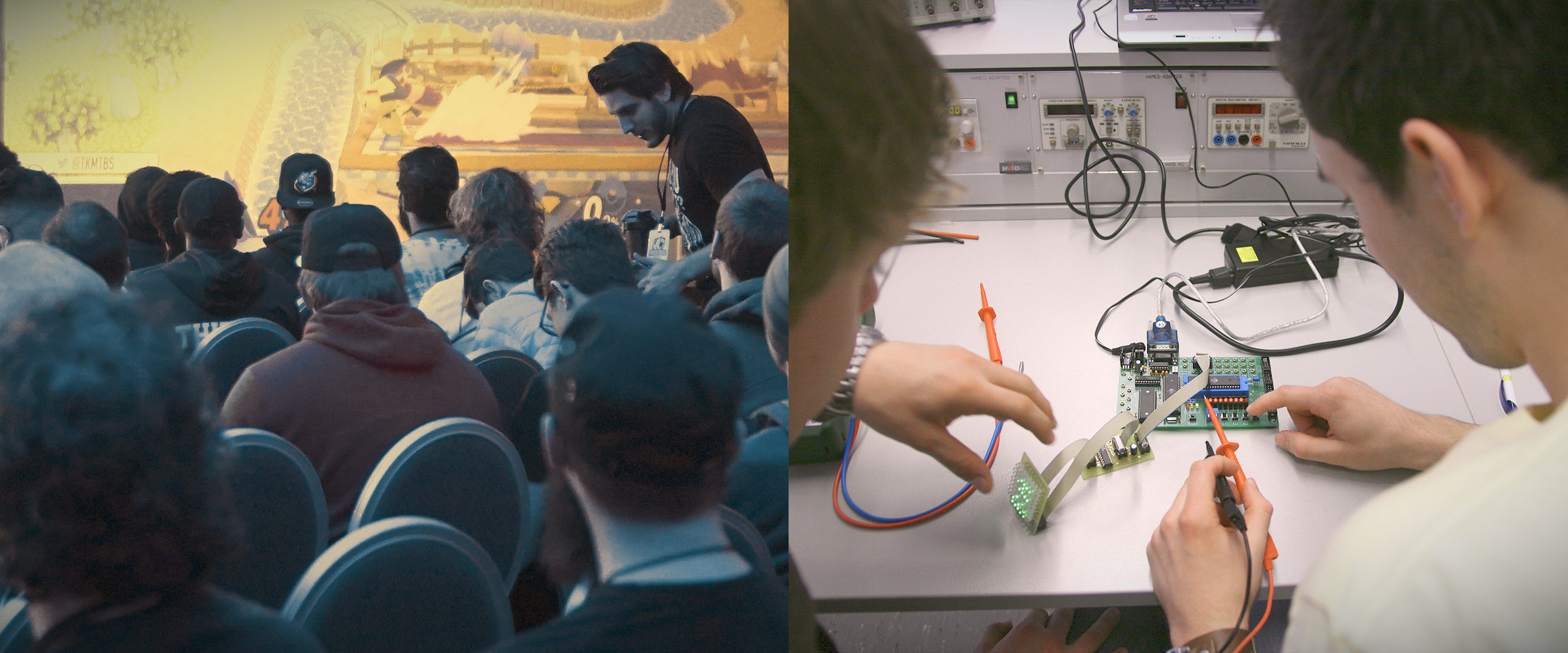

One factor that heavily impacts the social dynamics of the class is its size. Are you in a giant, first-year lecture hall at university? Are you in a community or private college with fewer students in each class? What about a much smaller, upper-level seminar class at university? Are you in a lab or tutorial where there are even fewer students?

As a general rule, we tend to acknowledge other people when we’re in a smaller group, especially if we have some previous acquaintance or common experience. When we’re in a larger group, we tend to ignore one another. Think of how people in small towns all tend to know one another, whereas strangers in big cities tend to carefully avoid making eye contact or acknowledging one another’s existence.

The same principle applies to college classes. Generally speaking, colleges and college classes do tend to be bigger than high schools or high school classes, so people are more liable to ignore one another. At universities, most social interaction happens outside of classes.

This is particularly true in giant lecture halls from big universities. My introductory psychology class had hundreds of students, and it wasn’t even at a particularly large university. In these classes, there’s no way that any student could get to know everyone, and under these circumstances, people are a little more prone to ignoring one another. That doesn’t mean you can’t interact socially in these lecture halls – often, people will sit in more or less the same place, chat with their neighbors in the first few classes,[2] thereby establish an acquaintanceship, and continue to have discussions afterwards as they continue to sit in more or less the same places. You might notice other students that you are already acquainted with. If you have some acquaintances in the class, you could ask them about setting up a study group.[3]

If there are fewer students around, or if the type of class is one with less silent listening and more class participation, there will be more social interaction. This might be the case, for example, in a science lab where people have lab partners, or a small humanities tutorial with group discussion.

Class Participation

This brings me to my next point: sometimes, students are expected to verbally participate in classes.

In general, with larger classes, there is going to be more silent listening – for the simple reason that there is not enough time for everyone to participate. If the instructor of one of these classes wants students to participate during lectures, they will probably ask students to use a device called the “iClicker” to respond to multiple-choice-type questions. During class, the instructor can pull up summary information showing the breakdown of the class’ responses, and afterwards, the instructor can use individual students’ responses to assign participation grades.

Some instructors particularly want students to be engaged, and they may give students opportunities for discussions in small groups or with neighbors – but it’s quite difficult to turn these discussions into grades.

However, there are some post-secondary classes where verbal participation in discussions is not only expected but where it is part of your grade. In humanities classes, there are often small tutorial sections, and participation in discussion is an essential part of these tutorials. The same is true of some advanced and graduate-level seminar classes. Because of the small size of these classes, it’s easier to assess participation.

Autistic people often tend to talk a bit too much or too little in these sorts of discussions. Talking too much is not necessarily as big of a problem as long as (1) your contributions are relevant and thoughtful and (2) you don’t speak so much that other students don’t get a chance to contribute. I tend to be a bit of a rambler so I sometimes ask instructors and teaching assistants to politely let me know if I am talking too much.

It’s a bit more of a problem if you aren’t talking enough, because that will hurt your grade. If you simply aren’t comfortable speaking in public, or if the discussion is conducted in such a way that you never have enough time to figure out what you want to say, you should probably talk to your instructor or teaching assistant*. Instructors usually want their students to do well, so they may be open to some alternative way of assessing participation, like a written reflection or a chat in office hours. They might also be able to adjust the format of the tutorial or seminar to make the environment more accessible for you. You can also ask the disability services office if they can provide you with any official accommodations to make the classroom environment more accessible.

*Note: not all in-class discussions must happen using speech. If you need or can contribute better using speech-to-text or other means, check in with your instructor or with Disability Services to use this as an option for participation

Conclusion

While I hope this article helps, I recognize that it doesn’t cover everything that might be relevant. In truth, this is because it can’t – the social environment of the university class is going to vary depending on your institution, the field of study, and even the quirks of particular instructors and students. Ultimately, you are responsible for gathering your own information and advocating for yourself, so you’re going to have to figure out the class culture from observation, which is one of the reasons why I suggest taking some time to tour the campus environment. But I hope this post covers a lot of the most important differences between K-12 school classrooms and university class environments, as well as some of the differences between different types of college classes.

If you can think of any other relevant factors about university classes, I encourage you to add them in! Please insert them, or any questions you might have, in the comments section below.

[1] Most university instructors will have a doctoral degree, although you will sometimes see a graduate student teaching. Many instructors will be sessional instructors, which means they are not technically professors. Your teaching assistants are graduate students, which means they are neither professors nor doctors (so they’ll probably ask you to call them by their first name). If you’re unsure whether somebody is a professor, a doctor, or neither, look them up on the university website.

[2] Conversations often begin with finding some common ground. Speculation about whether a class will be good or not could be a useful start.

[3] If you don’t have acquaintances but you still want to create a study group, you could investigate the possibility of proposing one using the course website (e.g., CourseSpaces, Moodle, Canvas). There might be a discussion forum you could use to contact other students – you might even find that someone else has already created a study group using the discussion forum. However, it is probably a good idea to make sure that people in your institution and program check and use these discussion boards; sometimes course websites contain extraneous content.

What types of self-care routines have worked for you? Are there any activities you are eager to try?

Let me know by leaving a comment below!

Appreciate Patrick’s insight? Consider learning to combat sensory sensitivities on campus or reading this guide to lists, schedules, and calendars.